A Mother's Trauma, Djinn & a Plague of Untold Histories (Part Three of a Story Series)

Lifestyle

|

Mar 23, 2022

|

16 MIN READ

Image source: Landsay Poetry Magazine

Editor’s note: We’re trying something new for you here at The Haute Take. Dr. Uzma Jafri, one of our “Mommying While Muslim” writers, has written a fictional short story, which we are presenting to you in three exciting installments. Read Part One, which debuted in January, here, and Part Two, which came out in February, here. This is Part Three, the conclusion. We hope you enjoyed this short story! If you did, let us know and we’ll bring you more similar content!

By Dr. Uzma Jafri

“You’ve got straw in your head,” hissed Munni.

Sarwat slunk closer to Sultana to stay out of reach. “I don’t. Dood Kaka said…”

“Dood Kaka is no friend of ours,” said Rahmat curtly, and continued rolling the roti out for their unexpected guest. Even one extra roti was hard to provide with their financial straits, but Ammi was sleeping off her episode and would not eat tonight. It would even out, and they could save face in front of their guest. As disheveled as he was, he was still to be honored in their house.

“I left him at the mandi*. How did he know where to find me then? He has to be …” Sarwat bit her own tongue realizing her mistake.

She forgot to stay out of Munni’s reach. In a flash, her braid was yanked back by her feisty sister, who demanded to know what she’d been doing with a stranger at the mandi. Sarwat had no choice but to report what happened at the riverbank when she fled her room that morning. Sultana fixed her eyes on Sarwat and uncharacteristically didn’t urge Munni to let go. As white as her knuckles were around the spoon over the fire, Sarwat suddenly feared being struck with the hot metal, even though her oldest sister had never raised a hand to her.

Sultana blinked quickly, looking at the bubbling daal* on the fire and hissed, “Do you have any idea what could have happened, you stupid girl?” Sarwat could see tiny flecks of daal fleeing into the air and onto Sultana’s face, flecks she didn’t even wipe off or flinch from their burn. Sarwat’s greatest fear was that Ammi would learn of her escapade into a stranger’s tent by the riverbank and would tear her in half, using the djinni’s* strength to get the job done.

“Get out,” ordered Rahmat. She pushed Sarwat through the curtain and into the main room where Hussainbi was chatting happily with the fakhir djinn*. Although she knew her usually quiet, strong sister was angry, she felt the meaning of her name – mercy – as she was pushed into the family’s communal space, to the safety of Hussainbi and their guest.

“How hard it must be for you without your people,” Hussainbi clucked to him as she lifted a hot tin cup of chai to her lips. The steam’s tendrils danced around her nose, disappearing into the chaadar* over her head. Sarwat wished she could do the same, hiding in the coolness that was Hussainbi’s countenance.

The fakhir* hung his head, letting his chai cool as he balanced the cup between two index fingers. He seemed cleaner now, and Sarwat thought he might have gone to the well or even as far as the river to bathe. He seemed to note her assessment and said, “I used the balti* outside to prepare for maghreb*.” Their small rear courtyard was where the girls bathed regularly or made their wudu* so the older ones could uncover their hair with some privacy.

Old jute sacks and the threadbare carpets of Ammi’s employers hung from jute rope on three sides as makeshift curtains. Sarwat felt a pang of, what was it? Anger? That a man had entered their sacred spaces so easily stung in a new way she hadn’t felt before. The imam and hakeem never made wudu in their home because it required crossing the main room and into their sleeping one, which Sarwat had escaped earlier that morning. It was too intimate a journey to make in someone’s home without invitation. And Ammi was sleeping in there!

“What a good man you are to prepare for the imam in this way. He will be so happy to see you and so happy to help you find your family,” breathed Hussainbi over her chai cup, cooling the still hot liquid and sending puffs of steam toward Sarwat.

Image source: Landays Poetry Magazine for Afghan Women

Eyes lowered, Sarwat asked, “Did Ammi wake up yet?”

Hussainbi shook her head. “No, my daughter. Not yet but Insha’Allah she will soon, in time for a roti or drink of water. I don’t think she was able to drink anything Rahmat tried to put in her today.” If she meant “while Rahmat doused Ammi’s screaming face with bowls of water,” Sarwat doubted that any fortification of thirst took place.

The older girls entered with their heads covered, eyes lowered, and with the faintest of salams, they laid the steel plates of roti, half an onion, and a bowl of daal in front of the fakhir and Hussainbi before disappearing. Hussainbi beamed proudly at her girls, so well trained and hospitable, just as her dead daughter in law had been. Her face never revealed her old pain, however, and she quickly urged the fakhir to eat. “The adhan* will sound soon. Hurry and eat and you can follow the men to the masjid.” She pulled her gray shawl off and handed it to him. “You can wear this over your clothes. It was my son’s.”

Sarwat knew appearances meant much to Hussainbi, who was one of the Big House dwellers before the flood. That‘s how she knew so much about the other side of the river where they rarely ventured. That was how she could summon the hakeem who had been on her payroll once upon a time, who now came in deference to their old relationship, paid in Hussainbi’s prayers as he attended Ammi.

Hussainbi was kind, though, and never aired what she once was or had because as she said, “The water washed everything away. We all have just six feet in common together now.” She likely wanted the fakhir to have some cover for his still-soiled clothing and would literally give him the last of what she had to save his dignity. She’d been doing it for Ammi and the girls for so long.

Despite looking desperately hungry, he ate slowly and Hussainbi raised a brow to Sarwat, her cue to disappear with her sisters where they sat behind the curtain, sharing a roti and the other half of the onion. Sultana handed her a fresh roti and bowl of daal. “You need to eat so you can make better use of your brain. Take it.”

Image source: Landays Poetry Magazine for Afghan Women

Rahmat didn’t look up and covered her bare arm with her chaadar. Sarwat saw at least 3 lines of red, torn skin and knew it was the djinni who had left these scars on her. Poor Rahmat and her scars. The blotches from the plague and now these lines together would make a bagh* of her arms. Out of so much disease, something so pretty made Sarwat smirk.

“You don’t have any shame, huh?” Munni snapped at her.

“Sit down and eat,” Sultana commanded both of them with Ammi’s countenance upon her. As the light dimmed outside, she looked more like their mother. She shook her head as Sarwat pushed the bowl of daal toward Munni and produced another one. Their only other one. The older sisters always sacrificed for their younger ones, and it was commonplace for them to take smaller portions. So much so that Sarwat didn’t even feel guilty about it anymore. It was as they had always lived.

Munni ate her warm roti in hot silence, sparks leaping from her knee when Sarwat accidentally brushed it. She didn’t know why this sister was so irritated by her, but suspected it was because Munni was so brave while Sarwat feared her own shadow. It wasn’t just today that she attracted Munni’s wrath, but it was often enough that she knew she should stay closer to her older sisters. Yet hadn’t she proven today that she was brave enough to leave home for the river by herself?

“Sometimes it isn’t the water, but people who are more dangerous,” whispered Sultana. “You will not go to the river alone again.”

Sarwat nodded as she chewed, making sure her sisters noted it.

“How could you be so stup …” and Munni was flicked quiet by Sultana’s fingers.

“Enough. She didn’t do it before and she won’t do it again. We have enough to worry about with Ammi. Now Hussainbi brings this fakhir to take care of.”

“Appa, he’s not a fakhir,” offered Sarwat.

“Then who is he?” hissed Munni.

“He came from the West for his family.”

“His wife? His children?”

“I don’t know.” Sarwat retraced this morning’s conversation with him and realized that in fact she did not know.

“You don’t know?” Munni sounded incredulous and even Rahmat looked up in surprise.

“Did you give him anything?”

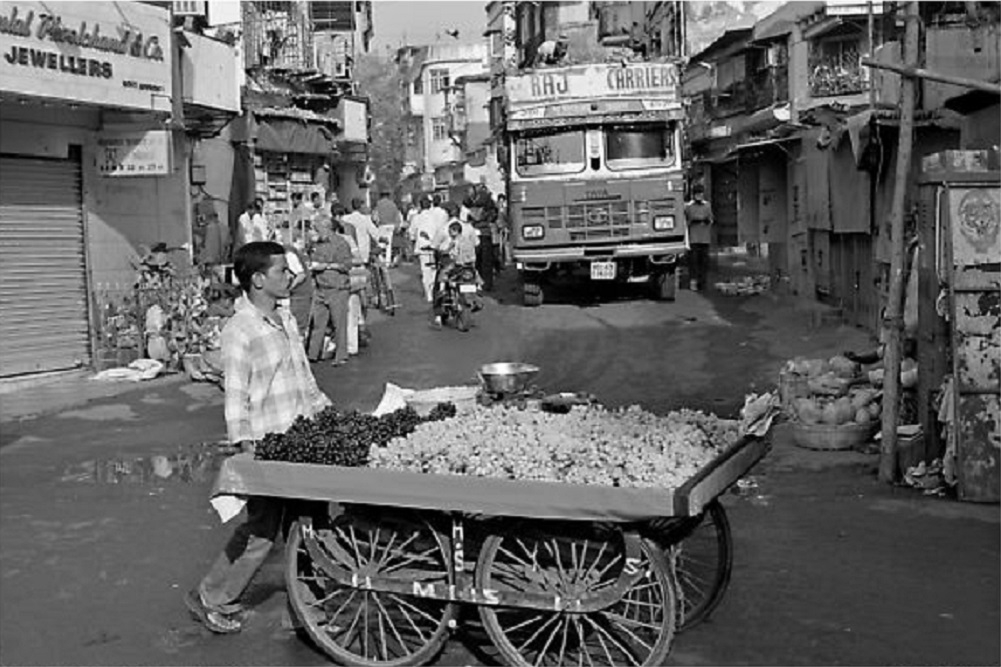

A fruit-cart in Pakistan; image source Google free images

“No. What do I have?” Sarwat was offended now. How stupid did they think she was? All she owned was her mirror and she would put up a fight than give it up to anyone. A weak fight, given the plague left her punier than her peers, but a fight nonetheless.

Rahmat nodded and began to clean. Her slender fingers belied their strength as she quickly cleared their area before adhan. On cue, the muaddhin* called for prayer, and Sarwat covered her hair with a chaadar. They would soon hear the men clambering through their short doors to the masjid, a thatched roof building just up the gully on higher ground. They heard their own outer door open and knew the fakhir was gone as well.

Sarwat took her leave to Hussainbi and sidled up to the grandmother figure seated on the jaanemaz*, ready to worship. “Why did you bring him here?”

Hussainbi’s eyes opened as her lips continued to move in du’a. She raised her eyebrow with an upward tilt of her chins, invitation to tell her why Sarwat wanted to know.

“I met him today. I think he followed me here. He’s looking for his family and for work, but I told him Abba is dead. We don’t have work for him.”

Hussainbi furrowed her brow and continued to move her lips in silence. “He came to my thela* today asking for his Pari* and her children. I don’t think he’s looking for you.” She raised her hands, eyes closed for a short du'a and wiped her face with her palms. “Daughter, maybe he has work for us.”

“We don’t need work from him,” Sarwat retorted. “What work could he have anyway? I don’t think he’s eaten anything in days.”

Hussainbi chuckled as she stood for salah*. “My liver, my life,” terms of endearment she used sometimes. “Maybe that’s the work he’s giving us?” She raised her hands to pray and Sarwat saw her cue to do the same. She wasn’t going to be as fervent as she knew this grandmother would be. Her mind was too preoccupied with what the fakhir djinn wanted with them, and who Pari was.

By the time they finished praying, stirring in the sleeping room caught their attention and Sarwat entered behind Hussainbi, the first to take over a situation. “My daughter, how are you?” she cooed.

Ammi rubbed her head and winced, observing her shredded knuckles. “What did I do?”

Hussainbi clucked, “Nothing, my child. The girls controlled it, and Hakeem Sahab will be here today to take care of it. How is your tongue?”

“It hurts,” Ammi stuck it out for observation and Sarwat could tell it was bruised if it wasn’t cut at the side. There was no fresh blood in her mouth at least. “I bit it again.”

“A trial for you, beti*, a trial for all of us.” Hussainbi held water for Ammi, encouraging her to drink, and nodding to Rahmat to bring some food. A knock outside and a call to request entry reminded them of their guest. “Come in!” commandeered Hussainbi.

As the youngest, Sarwat skipped to give salam and welcome the imam and fakhir djinn. The latter looked much cleaner, wearing a gray kurta he must have received from someone at the masjid. “I’ve been looking for you,” he said as he smiled.

Sarwat huffed. Where was Hussainbi when she needed her to witness that she was right? “You know where we live now. You found us easily, I’m sure.”

Imam Syed raised an eyebrow at her tone and reminded the room, “Guests are from Allah, beta*. Treat them like He sent them.”

Sarwat motioned for them to sit and padded her way back to pout for chai from the older girls who’d gone to the sleeping room to check on Ammi as well. “He’s back.”

“Who’s back?” asked Ammi finishing her roti as Hussainbi took account and kept urging her to finish all of it.

“The fakhir dj…”

Hussianibi interrupted deftly, “Tsk, tsk, we don’t call people that. His name is Gul and he is from the West looking for his family.”

Ammi stopped chewing. “His wife?”

“Yes, I think so. Her name is Pari and he thinks she died in the flood. Imam Sahab will take him to the hospital in the morning to go through the papers to find out.” Hussainbi was now directing Rahmat on chai preparation for the guests of Allah (S).

Sarwat noticed her mother’s hands trembling. So did her sisters. “Why would he look for her now? It’s been so long.”

“I think she was gone.” Husainbi scraped sugar out of a steel can. There was a thin film of it in there she wanted served. She handed the cups to Munni to serve the guests outside.

“She left him?” Ammi pursued.

“Beta, I don’t know. He’s outside if you want to speak to him, but I think you should rest after today.”

Ammi cleared her throat and covered her hair, nodding to Sultana who glided over to help her stand. With a loud salam, she exited the curtain and into the main room, ignoring Hussainbi’s objections.

Mousee river

Sarwat heard the steel cup fall before she saw Gul drop it. He stared open-mouthed at her mother, something no one in Tareekhgardh dared do. There was a mix of fear and grief in his face, but also happiness, and it surprised Sarwat to see how easily a face could demonstrate all of these emotions at once.

“Pari?” he whispered.

“Why are you here now?” she demanded icily, in a tone Tareekhgardh was familiar with.

Gul wiped his eyes and smoothed his beard. “I’ve been looking for you.”

‘Was this the only thing he knew how to say in a scary moment?’ thought Sarwat, but she blurted, “You were looking for us for work. And for your wife.”

Gul couldn’t speak and Imam Sahab offered, “Beta, his sister and her family came here many years ago. After he told us at the masjid who he was looking for, I told him I think it is Hajja Farhana he wants to find.” He turned to Ammi, “Do they call you Pari?”

Ammi did not take her eyes off Gul. “They did. That’s what they wanted me to be. And when I didn’t listen, they cursed me.”

“No!” Gul waved his hands in protest, looking from the imam to Ammi and the girls. “No, no, we didn’t. We made a mistake and didn’t explain well. We only wanted to keep you safe, Pari. He didn’t know how to take care of you, but we would never curse him. Ammi and Agha respected him. I respected him.”

Ammi’s eyes darkened and Sarwat hid behind Sultana. “So much you broke his arm? You locked me in the house, away from my husband? That was respect? Then what did your hate look like?”

Gul did look scared now as the imam turned on him, horrified. “I did. I did do that, but I didn’t mean to. I was trying to convince him to let you stay. We could take care of you together. Ammi locked you in the room because she was desperate. She didn’t want your illness …”

“I’m not ill.”

Hussainbi stood behind them absorbing all of it until then. “Yes, you are, beta. Since Muiz….since the flood.”

Gul nodded as Ammi’s eyes flashed in hatred. “No,” she retorted. “He made me better. But then she came.”

“Who?” Gul was genuinely confused.

“The one who wanted him. Because he took care of me. Of us.” Ammi had tears in her eyes, but even they appeared too scared of her to fall.

Image source: Landays Poetry Magazine for Afghan Women

Hussainbi took a seat on the floor and motioned for everyone to do the same. “When we are angry, we should sit, when we are sitting we lie down. Gul, what sickness does she have?”

“Mirgi*,” he replied simply, avoiding Ammi’s eyes.

“I don’t. Hakeem said I don’t.”

“You did when you were with us. Since you were a child. It got worse as you grew older, though. Not as many spells, but when the daura* came, it became stronger, longer. Sometimes you would stop talking, moving, eating. You slept for days. Ammi and Agha prayed and sacrificed so much for you to get better. They were so happy when you got married because they thought you were cured. But then it happened again.”

“Because I was going to be a mother,” interjected Ammi, startling Sultana. “It was stressful because we had to leave for the assignment. Before that Muiz made me better. I was cured of it.”

“Maybe. But Muiz was scared and didn’t know what to do when you got sick again. We helped him take care of you, gave you the right tea, avoid the town gossips who said you were possessed. You remember how they talked. Then we encouraged him to stay, but he wanted the money.”

“A life. He wanted a life for his children and me.”

Gul held his head in his hands. “Agha died of a broken heart. He died calling for you, sister.” At this Ammi’s breath caught. “Now Ammi cries for you. She thinks you died in the flood. I came looking when she sent me. First the railroad, now this spoiled, drowned city. I have to tell her I found you and your children.”

Sarwat couldn’t understand what Gul was saying. As long as she’d had memory, Ammi was possessed by a djinn, a deal she made to save her daughters. Now to think that all along, her mother had a disease that could be cured made her angry at Jahangir Hakeem. Why hadn’t he fixed her?

“Then you are a blessing. Insha’Allah with your help my daughter will be cured and happy again,” exclaimed Hussainbi. “What shall we do for her?”

“There is a tea. My mother collected the herbs herself, and our hakeem made the tea for Pari. As long as she drank it every day, we wouldn't see her sick for many months, as long as a year. Did you stop drinking it?”

Ammi looked away at last. “We couldn't find it here. Muiz asked the hakeem in Secunderabad and here, but they didn’t know how to find it. They heard about it, but they said to make du’a and give sadaqah*. Not to tell anyone or they would say I was possessed. Muiz took care of the children when I was sick, took care of the house, of me. He died taking care of me.” She wept into her chaadar, her tears relenting in spite of her.

Old script depicting a seizure disorder; image source: author.

Sultana stroked her back. “He died because of water, Ammi.”

Sarwat felt small and afraid, and a little bit hopeful. “So there is no djinn?”

Hussainbi pulled her into a hug. “There are, beta. Just not here. Not in your Ammi.”

Sarwat didn’t know what relief was until she cried into Hussainbi’s shoulder. Relief that her history made sense. That her mother was like everyone else, not a djinni, not a speed traveler or woman of steel. Being ordinary was what Sarwat wanted all this time.

“Come, we should go to your mother, beta,” urged Hussainbi stroking Ammi’s head. “She is old and it will take us time to get there. She can teach us how to stop your daura.”

Ammi appeared crushed. “But Muiz. He’s here,” she choked.

Hussainbi’s eyes glistened as she stroked Ammi’s cheek and held it. “He’s with Allah, my jaan. So wherever you go, Allah is there. Wah*, look. Muiz is there, too. You have to live because you said yourself: He wanted a life for you and the girls.”

Quiet Rahmat fell to her knees beside Ammi to hold her, but Ammi pulled her daughter’s arms to her lips, watering the garden of scars on them with her tears. While Ammi begged her daughters’ forgiveness as they crowded her, finally knowing her secret sickness, busy Hussainbi discussed travel and logistics with Imam Sahab and Gul.

When it finally came time to load their tanga* and head West toward the Kush later that month, the gully crowded around them to bid farewell. Most of the neighbors were still wary because they didn’t believe that all this time Hajja Farhana had been afflicted with mirgi, but anyone coming or going was newsworthy and worth a welcome or a cast off. Hussainbi was also leaving the land of her ancestors for the land of Ammi’s.

The mean girl who Sarwat had beaten at noondi* was among the crowd, scowling, no doubt from jealousy. Sarwat bounced over and gingerly offered the mirror to her.

“It never worked for me,” she explained.

The mean girl cocked her head. “What do you mean? It works fine.” She checked her reflection and Sarwat saw her scowl perfectly.

“I never saw myself in it.” Smiling, Sarwat handed it over and raced back to her story.

Author's note and some historical background: Mass migrations of Pashtun occurred from Afghanistan to India as early as the 11th and 12th centuries, largely due to Muslim empires and dynasties they founded or helped found on the subcontinent. They served on the Indian subcontinent as traders, politicians, religious leaders, and soldiers under Mughal rule. Under Ottoman rule, it was not uncommon for inhabitants to travel within the empire, intermarry, and migrate to other parts of the empire.

One such story occurred in the author's history, the Afghan mother lost to history and her ultimate delight or demise unknown. In honor of her and other mothers lost to death, fate, illness, or the histories of men, this story took shape. Family legends, gossip and many maps of Hyderabad were relied upon to create Ammi and Sarwat's herstories, but neither exist in reality and any similarity to a known place or person is purely coincidental; Tareekhgardh is a fictional village in Hyderabad, but it very well could have existed because there are so many lost in time and name due to the political and economic upheaval of the region.

Intermarriage and migration, chronic illnesses, preoccupation with djinn possession, as well as the Musi River flood of 1908 and its effects on Hyderabad Deccan informed this fictional story.

Glossary:

Adhan: call to Muslim prayer, usually announced via minaret

Bagh: garden

Balti: bucket

Beta: son or child

Beti: daughter

Chaadar: bedsheet or large head covering used by women in subcontinental India

Daal: lentils

Daura: seizure

Djinn: creation of Allah made of smokeless fire, also with free will like humans

Fakhir: beggar

Fakhir djinn: beggar djinn

Insha’Allah: God willing

Jaan: life, energy

Jaanamaz: prayer mat

Kus: Hindu Kush mountain range of Afghanistan

Maghreb: sunset prayer

Mandi: open street market

Mirgi: epilepsy

Muaddhin: person assigned to call the Muslim prayer

Noondi: hopscotch

Pari: angel (f)

Tanga: horse or donkey-drawn cart

Thela: cart

Sadaqah: voluntary charity in Islam

Salah: Muslim prayer prescribed five timesa day

Wah: wow

Wudu: ritual ablutions preceding Muslim prayer

Dr. Uzma Jafri is originally from Texas, mom to four self-directed learners, a volunteer in multiple organizations from dawah resources to refugee social support services, and runs her own private practice. She is an aspiring writer and co host of Mommying While Muslim podcast, tipping the scales towards that ever elusive balance as the podcast tackles issues second generation Americans have the voice and stomach to tackle.

Subscribe to be the first to know about new product releases, styling ideas and more.

What products are you interested in?