A Mother's Trauma, Djinn & a Plague of Untold Histories (Part One of a Story Series)

Lifestyle

|

Jan 13, 2022

|

10 MIN READ

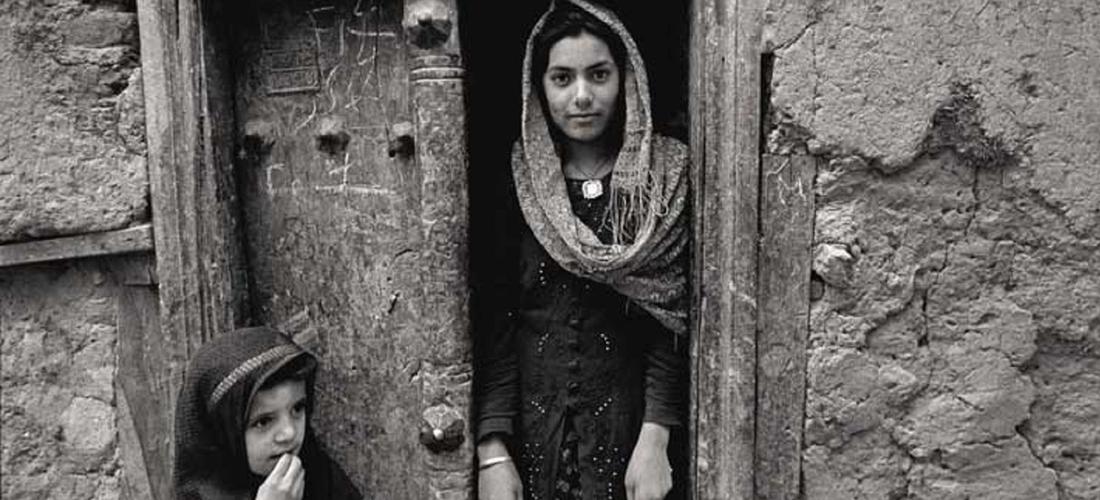

Image source: Landsays: Poetry of Afghan Women

Editor’s note: We’re trying something new for you here at The Haute Take. Dr. Uzma Jafri, one of our “Mommying While Muslim” writers, has written a fictional short story, which we are presenting to you in three exciting installments in January, February and March. We hope you’ll enjoy it and will come back to read Parts Two and Three! And, if you enjoy this, let us know and we’ll bring you more similar content!

By Dr. Uzma Jafri

It was not often that Ammi banished Sarwat to the back room, but when she did, it was to protect her. Sarwat knew this too well, and was glad for refuge from the wrath of the djinni* she knew slept deep inside her mother. At least she thought it was a djinn. Hussainbi, the fruit vendor and their self proclaimed Nanijaan*, said only female djinn could carry on like Ammi did. Sarwat was relieved at least this time Ammi gave her fair warning to hide.

The ladies at the water tank often tittered about it, and Sarwat and her sisters acted as if they could not hear. While it left them essentially friendless, it also protected their family. They knew this with the wordless wisdom of children even before Hussainbi entered their lives a few years ago. No one dared cross Ammi, or “Hajjani Farhana,” as she was known in Tareekhgardh, their home since Sarwat could walk. “Hajjani'' was a title for those women who completed the sacred pilgrimage. A village couple reported to the neighbors that they had seen Ammi at the Holy House thousands of miles away.

The neighbors gasped, “hai hai,*” that they’d seen Ammi taking in her morning milk pail every day while the couple was gone. Dood Kaaku verified that it was Ammi herself who received the milk, emphasizing the strange music of her accented Urdu, her hazel eyes and white skin evidence of all that had been burned clear by the fire of the djinni. When he found out she had also recently been spotted in Saudi, he didn’t deliver milk for the rest of the week.

Word quickly spread that Ammi could travel at the speed of light to tend to her children’s breakfast and perform her Hajj pilgrimage on the same day. Her power was accepted as fact, revered as myth and feared as lore, and that was what Sarwat was born into – daughter of a woman possessed. Prior to that, Ammi was only a widow transplanted from the west, possessed of djinn and four daughters; cursed, to be exact.

As noise escalated outside the flimsy jute* door and dust lifted the curtain in front of it, Sarwat turned her back to the impending onslaught and focused again on her mirror. It was blurred and cracked, a remnant of a hand mirror she won in a game of nondi* from the meanest girl in Tareekhgardh. The girl hadn’t bullied Sarwat herself, knowing whose daughter she was, but her upper lip curled in a sneer she barely tried to hide.

“You won it. Take it,” she said as she pressed the broken mirror deep into Sarwat’s palm. The edge was blunted with time, so it didn’t slice her. Instead it left a deep red indentation that smarted for hours, but Sarwat didn’t even mind because she’d won something for the very first time. She was six years old at the time.

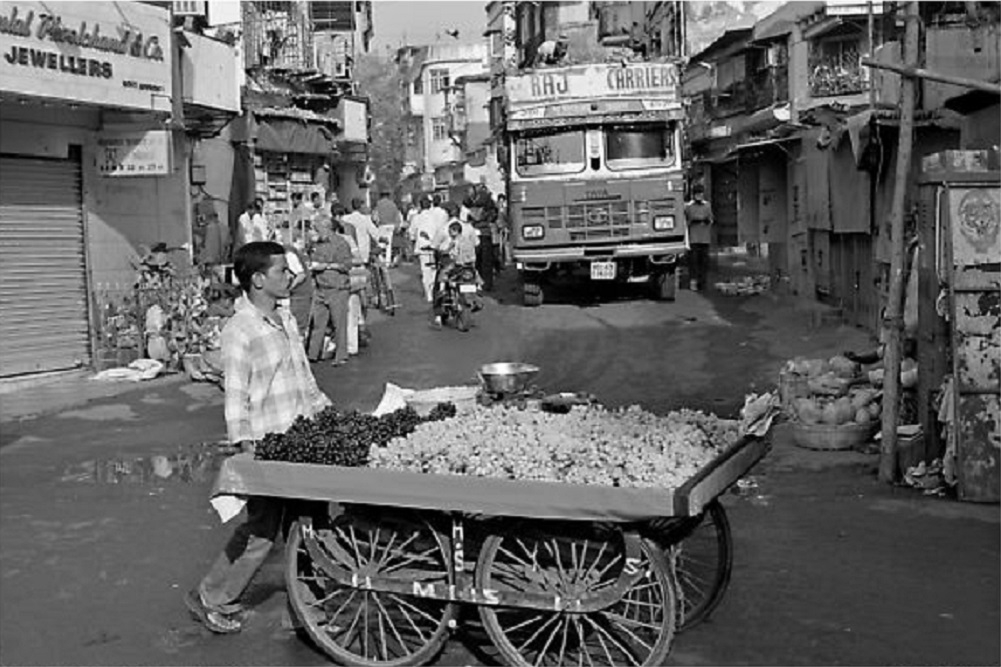

A fruit cart, or tehla. Image source: QT Luong / terragalleria.com

Since then, she’d learned that looking in the mirror showed her a land with silver cities in it, people riding in noisy tehlas* without any animals lugging them forward. How fast they moved compared to Hussainbi’s tired donkey leading her sagging thela to their town’s mundi* twice a week! Although the women in the mirror had full cheeks, they looked sick as they sat idly in their thelas or on their thakts* in large halls. Even her mother, who sighed wearily albeit rarely through life in between djinni attacks, looked happier than they did.

Once Sarwat asked Sultana what the pictures in the glass were, but her oldest sister looked quickly up and over her shoulder before warning, “You’re Ammi’s daughter. Don’t tell anyone, and hide that.” She motioned toward the mirror and whispered an “Astaghfirullah” under her breath as they milled flour by hand behind their home.

Sarwat dared not ask Ammi for fear that she would accuse her of stealing it from one of the houses where they accompanied her everyday to clean. Instead, she enjoyed the streaming pictures in the glass and wondered how she could learn the names of the things she saw in it.

Her reverie was sliced by the sounds of blood curdling screams and clay cracking. The fever she had from several years ago had left her weaker than the others, and she could be of no help when Ammi’s djinni woke up. Even though one of her older sisters, Rahmat, still bore the red marks of the fever on her arms, she always stepped forward to protect Ammi during these times. The two eldest would pin Ammi’s arms behind her while Munni ran for the imam and Hussainbi to come.

Ammi usually broke free, because the strength of the unnamed djinni was beyond what two young girls could physically confine. It had been a long time now since the djinni appeared, but when she did it was to strangle the girls, beat the dry clay walls until they were stained with bloody palm prints, and throw dishes in the small house while shouting curses in languages they did not understand. She would throw one of the girls if she could, but by now Sultana and Rahmat were taller than Ammi and experience taught them to keep out of reach. The girls could see it was just Ammi trying to plead with the djinni to exit her body and return to the western side of the river where they’d tried to leave her.

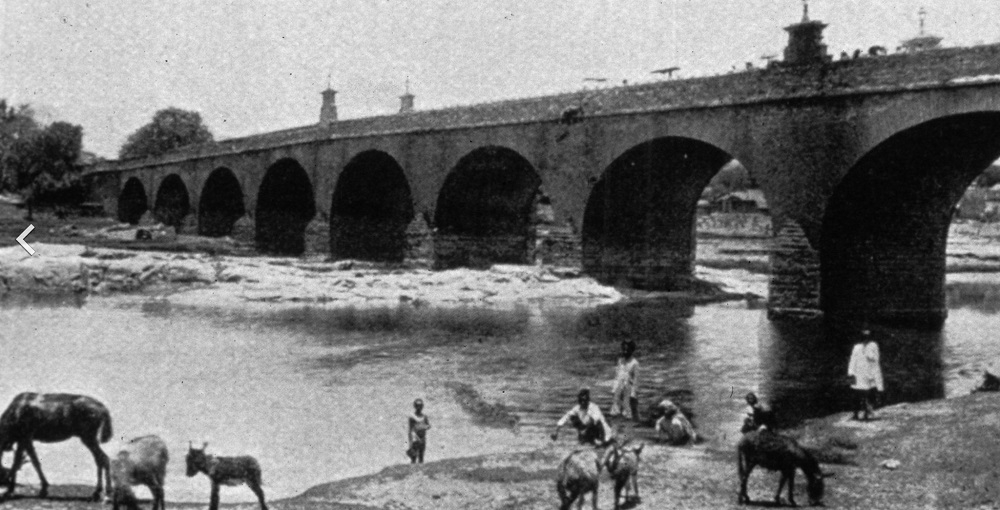

Mousee River; image source: the author

Soon Hussainbi would arrive and sit on Ammi’s chest, splashing donga* after wooden donga of warm water on Ammi’s face, while Imam Shahid prayed loudly to drown the sounds of Ammi’s choked, unintelligible shrieks and the older girls watched in fear from the entrance. Light footed Munni sprinted to and from the well to replenish the water. Munni admirably did not care who saw her, only that Ammi would be freed.

Unlike her anxious, caring sister, Sarwat hated being stared at by the neighbors after one of these episodes, all of which could be heard by each and every person in the gully. They weren’t witness to their mother’s struggle to tame the evil inside her. The women in fact busily and loudly took notes to discuss with Dood Kaaku in the morning, and to share again with each other at the water tank later. Already Sarwat could imagine their pallus* covering their mouths in feigned concern for Ammi, but she knew it was because they were upset they couldn’t see the tamasha*, a break from the monotony of their daily lives.

Wrapping her mirror in the hem of her kurta, she unclasped the shuttered window to jump outside into the tiny courtyard. Behind their home was the railway, the one thing that could be of use now when Ammi was so loud and frightening. Of course the trains only ran late in the afternoon into the night and Ammi slept right through them. The djinn were supposed to be awake at night, but Ammi’s preferred a proper daytime spectacle. Sarwat didn’t seek bravery, duty or praise like her sisters did. She wanted to run away.

Their family had just returned some weeks ago from the bridge after the latest plague outbreak forced an evacuation. Ammi insisted they leave their precious chaadar* held in place as shelter on the banks. “No plague leaves forever,” she murmured, as they packed to go back home to their dark brown gully, hidden behind metal doors and within clay walls. It was Sarwat’s first evacuation, but her sisters had been there years before for the last one when Abu was still alive.

Ammi’s anguish when the authorities forced them to the river this time left her quiet and contemplative once they arrived there. All the fight left her, and Sarwat almost wished the djinni would wake up then and show the men they couldn’t force them out of their house. But once in the open air by the river, Swat was so glad the municipality made them come.

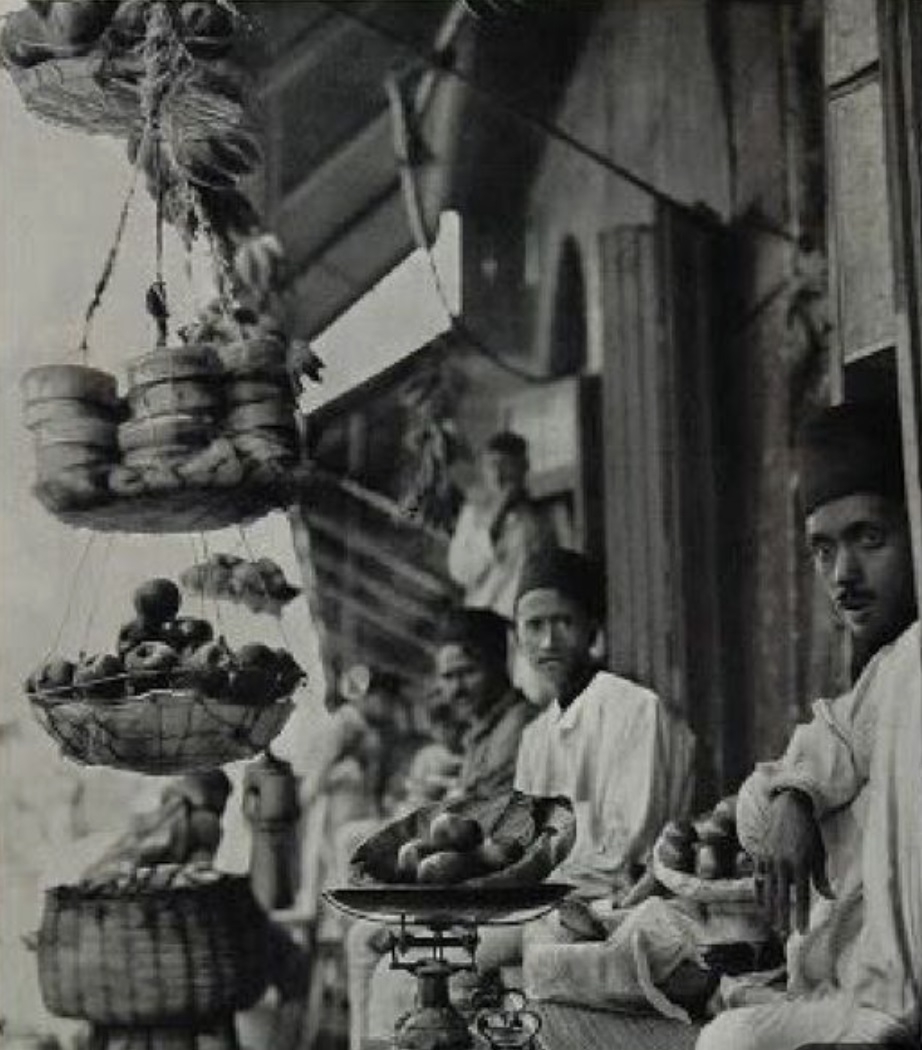

Fruit mandi; image source: the author

During the outbreak, they’d had nothing to chase, chop, grind, fan or sweep for weeks. All of Tareekghardh and even towns they hadn’t seen shared communal meals, slaughtered and cleaned chickens, prayed outside, and washed their clothes on the banks of the Mousee. Neighbors who avoided them in town made sure they had a warm roti at meal times and were accounted for at night in their makeshift tents. Hussainbi stayed in their tent, having no family herself, and taught all the little girls in the quarantine camp folks songs and how to beat different melodies on the bottoms of pots and stretched cloth.

Ammi never left the girls’ side for the weeks they spent there, her lips constantly moving in prayer. But some nights they heard women splashing and laughing in the river.

Ammi slapped her head hard when Sarwat asked what the women’s words meant. “Go to sleep. You worry about nonsense,” she whispered, with a smile at the corner of her stern mouth. It was the only time in the quarantine that Ammi looked anything but apprehensive.

Too soon it was back to work in town, which was harder now that so many people they’d left there were gone. Customers were scant for all the grain Ammi milled or the rice she’d picked clean, and the houses she cleaned west of their town near the palace lay empty. Sultana sighed that these families were unlikely to ever return and Sarwat understood that they had died from the plague. She felt blessed that their family bore only the scars of typhoid on Rahmat’s arms. They all walked farther and worked harder for far less since the evacuation, and Sarwat more fervently anticipated her stolen moments with the mirror. Ammi was the only one who seemed relieved to be back, until today when the post arrived in the morning.

As Sarwat approached where she thought the tents should surely be, her breath was shallow from climbing the small hill between the outskirts of Tareekgardh and the river. “Please, be there,” she thought, and quietly said, “Bismillah'' for good measure. Before her eyes fell down to the waterline, she heard distinct flapping and exhaled to see chaadar still strung between large branches staked into the ground. Her family hadn’t been the only one to leave behind a just-in-case shelter. She was where she’d rather be than in all the world. Only the silver cities in her mirror held more promise.

It didn’t matter if it was her own tent or not, so free did she feel from the burden of her mother and the gossip of neighbors. She bounded to one closest to the river where Ammi had refused to let them make camp, imagining the glorious nap she would succumb to as she dreamily watched her mirror listening to the Mousee flow outside. Ammi might be awake by maghreb*, and even so, she would not take into account where her daughters had been during the attack. If her sisters didn’t worry for her, Sarwa preferred to spend the night or even the rest of her life by the river, but she knew she had to make it home by sunset and still had several hours to escape.

Chaardarghat Bridge in the 1890s; image source: the author

Guilt flickered in her heart over abandoning her sisters, who must be cleaning up their mother and home, nursing their own bruises and cuts, tending to the chickens and milling, and preparing a meal. All while she ran away to daydream alone. She shook her head to dispel the guilt as she flipped up the corner of the hanging sheet.

Her excitement had preceded her, and she realized too late, endangered her. She should have aimed to go to their own chaadar left by the bridge. Ammi was adamant to keep the girls near her, warning that strangers would “sweep them away.” They only left her side for the few hours they could play in the gully with each other. Now Sarwat faced a fakhir* in torn kurta and white pajama grimed by time and travel. He sliced coconut meat with a curved knife the length of her arm. As he bent his head slightly to pick up the meat with his teeth right off the blade, he looked up.

“I’m so glad to see you. I’ve been waiting,” he smiled, chewing slowly with his eyelids closed, thoroughly enjoying the bite his frail body looked as if it needed. When he opened them to stare directly at her, Sarwat’s hasty retreat froze as fast as her entrance had.

She loved her mother immeasurably, the only parent she’d ever known, except when the djinni was in charge. There was nothing to hate about Ammi besides that. But it was Dood Kaaku who taught Sarwat and the people of Tareekhgardh to hate hazel eyes.

Running from a djinni landed Sarwat straight into the tent of a djinn.

Stay tuned next month for Part Two and Part Three coming in March. Share your thoughts on part one of this short story and what you think may happen (or should happen) in the comments below! Uzma may incorporate them into the next turn of the story!

*Glossary

Ammi: ”mom” in South India, primarily in Urdu speaking households

Chaadar: a sheet used to cover the head or for household purposes

Djinn: free-willed beings made of fire that exist parallel to humans, usually unseen

Djinni: female djinn

Donga: wooden serving bowl

Fakhir: beggar, poor person

Hai hai: lamentation expressed in fear, grief, shame, or shock

Jute: burlap, often woven into mats and household items

Kurta: long woven shirt, usually worn over loose pants, shalwar, or tight ones, pajama

Maghreb: the prayer performed at sunset

Mundi: market

Nanijaan: maternal grandma

Nondi: South Indian hopscotch

Pallu: long hem of the sari

Tamasha: spectacle or show

Tehla: animal driven flat carts, also flat pushcarts

Thakht: flat, hard bed or throne

Dr. Uzma Jafri is originally from Texas, mom to four self-directed learners, a volunteer in multiple organizations from dawah resources to refugee social support services, and runs her own private practice. She is an aspiring writer and co host of Mommying While Muslim podcast, tipping the scales towards that ever elusive balance as the podcast tackles issues second generation Americans have the voice and stomach to tackle.

Subscribe to be the first to know about new product releases, styling ideas and more.

What products are you interested in?