Where Does COVID Vaccine Fear Come From in Black and Brown Communities?

Community

|

Jan 28, 2021

|

6 MIN READ

Image source: Mother Jones and Twitter

Trigger warning: This article discusses medical experiments done on Black communities and may be trauma or fear triggering.

COVID-19 continues to ravage the nation and world. New pandemic surges, variants and viral strains threaten the health of billions across the globe while countries struggle to administer newly developed vaccines. Here in the United States, healthcare professionals continue to work to help the sick in an overwhelmed system.

For over a year, the virus has scourged through everyone’s lives, especially Black and People of Color (BlPOC) Americans, shedding a lens on entrenched systemic racism affecting the quality of care. The release of new vaccines offers one way to stem the massive tides of illness and death. However, many remain hesitant to get vaccinated due to concerns about the vaccine and stemming from an outright distrust of the U.S. healthcare system, one of the many social structures influenced by racism.

“The legacy of inequality and structural racism has led to unequal access to health care, schools, employment, housing and financial stability,” explains Dr. Ramla N. Kasozi, a resident physician in family medicine. I spoke with Dr. Kasozi about the legacy of medical racism, COVID and vaccination anxieties she encounters with Black and People of Color patients and why this is such a huge mistrust to overcome.

COVID-19 Issues Uniquely Impacting Black Americans

Being Black in America usually means that one cannot just live, be sick or die without encountering the country’s racial structure. Don’t believe me? Well, the internet is replete with articles about Black people harassed (and threatened with potential brutality and death through law enforcement) while birdwatching, eating lunch, barbecuing and sleeping. Recent Black Lives Matter protests represent a continuum of state-sponsored violence on Black people. The country is littered with segregated cemeteries and racism continues to influence funeral services.

Racism is an interwoven structure that affects every aspect of American life making it impossible for BIPOC to exist without having to deal with its negative effects, including when one is sick.

Despite the medical ethics of beneficence (promote the well-being of others), non-maleficence (do no harm) and respect for human rights, the real dangers of medicine for Black and Brown bodies remain undeniable. Dr. Kasozi explains how COVID-19 is the latest crisis to resurface medical biases.

Dr. Ramla Kasozi

“There is national data demonstrating communities of color (i.e. African Americans, Hispanics, American Indians, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, Asian Americans, Pacific Islanders) have been disproportionately affected by the coronavirus pandemic, owing to the existing social determinants of health and systemic racism,” says Dr. Kasozi, adding that “COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated existing health disparities so much so that Black or African Americans are contracting the virus at higher rates and are more likely to die compared to white individuals.

According to the APM Research Lab, 1 in 800 Black Americans have died (or 123.7 deaths per 100,000) compared to 1 in 1,325 White Americans deaths (or 75.7 deaths per 100,000). Several factors uniquely impacting Black Americans include, but not limited to:

1. Limited and/or inconsistent access to health care services due to employment stability and health insurance.

2. Inadequate housing conditions that are usually crowded and don’t facilitate social distancing, which stems from long standing redlining and racial residential segregation policies.

3. BIPOC are dealing with the burden of chronic medical conditions like diabetes, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and thus are at increased risk for infection.

4. BIPOC tend to work in essential fields that don’t allow for adequate social distancing. These include food services, nursing homes, janitorial, transportation and environmental services. This makes it difficult to work remotely.

5. Income inequality, discrimination, violence and institutional racism contribute to chronic stress in people of color that can wear down immunity, making them more vulnerable to infectious disease.

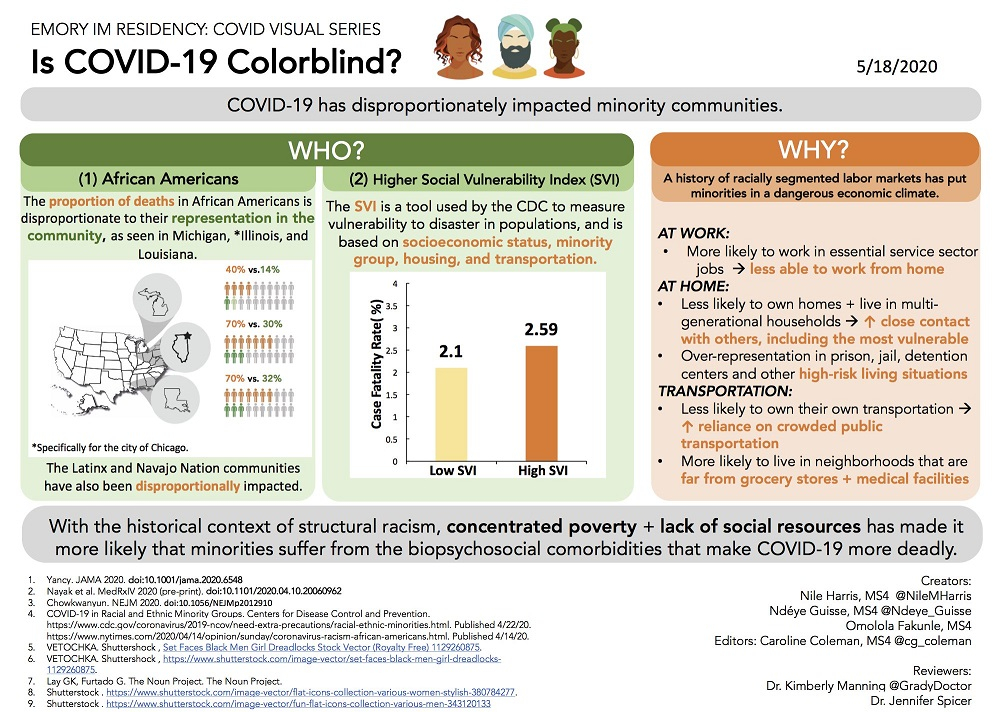

This infographic by Emory University medical students from May 2020 explains the impact of COVID-19 on Black Americans.

Vaccines and Distrust

In spite of the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on Black and Latino Americans, they remain the least likely groups to receive vaccines. A primary factor for the racial disparity regarding vaccination is the mistrust resulting from historical abuse at the hands of medical professionals and existing racial bias in American medicine.

The past affects the present, explains Dr. Kasozi, and medical professionals are only recently admitting to complicity in the country’s white supremacist underpinnings feeding distrust. “The dark history of experimentation on Black and Brown bodies, from slavery to present time, has played a role in Black Americans being worried about science and medicine.” Due to the recent murder of George Floyd, the medical community is finally admitting to its role in systemic racism, as evidenced by the recent apology from the American Psychiatric Association to BIPOC.

African Americans have also experienced a legacy of medical malpractice and extermination. James Marion Sims, the father of modern gynecology, butchered enslaved Black women during his tests and experimented on them without anesthesia. In the Tuskegee Experiment, doctors enrolled more than 600 African American men into their study and watched syphilis ravage their patients for 40 years, blinding, killing and driving them insane. Doctors didn’t treat the men even after recommendations to administer penicillin.

A doctor draws blood from one of the human test subjects in the Tuskegee syphilis experiment. Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

The Tuskegee Experiment ended in 1972, less than 50 years ago, which is when I was a child. With such atrocities still a part of our immediate experiences, there is no wonder why Black people don’t trust medicine.

Dr. Kasozi mentions that she receives justified pushback from her patients about vaccination and how she tries to validate their concerns and give them medical advice to help them make informed decisions. “For my BIPOC patients, I totally understand their hesitancy. I respect their opinions.

“I genuinely try to explain to them that due to gross health disparities caused by systemic racism, BIPOC have an increased risk of getting infected with COVID-19, [stemming from] the factors I mentioned above. [However], being infected with COVID-19 will lead to loss of work, loss of income, reduced access to health insurance, and the cycle of poverty will likely perpetuate. In the end, I make an effort to have shared-decision making discussions with my patients outlining the risks and benefits. The patient decides what is in [their] best interest. I will not judge.”

Dr. Kasozi serves as an example by getting a COVID-19 inoculation. “I am fully vaccinated. Working through the COVID-19 pandemic as a resident physician in Family Medicine, I have witnessed how this virus caused so much loss in Black communities. I’m a Black Muslim Woman. According to current statistics, a COVID-19 infection will [negatively] affect my livelihood and ability to provide for my family. Thus, the reason I decided to get vaccinated was to protect myself, my family and community.

Dr. Kasozi, her husband Dr. Denis Aiismwe as well as other Black Muslim healthcare professionals present a front to pushback against racial bias in medicine while acknowledging the physical and cultural distinctions that will increase the quality of care of BlPOC patients. We need them and all medical professionals to make healthcare safer. They understand why some of us are not quick to let anyone drive a needle in our arm and talk to us with respect, offering information and dignity.

Talk to your doctor about the COVID-19 vaccines. Do not be afraid to ask whatever you need to make an informed decision. If your doctor does not provide information or productive advice, find another one. COVID is not going anywhere, and it has proven to be a present danger. We all need to face the realities of life with COVID and weigh all of our options, including vaccination. Therefore, we should expect healthcare professionals to offer quality care and information to ease our anxieties and help us care for ourselves.

Subscribe to be the first to know about new product releases, styling ideas and more.

What products are you interested in?