Being Muslim in Public School - How Parents Can Effectively Communicate with Teachers

Lifestyle

|

Sep 17, 2019

|

10 MIN READ

By Nargis Rahman

It’s 8 a.m., and the kids are shuffling out the door to start their first day at their local public school. Their elementary school has about four Muslim kids in each class. Part of making sure they have a smooth year involves me staying in close contact with the teachers to express my needs and concerns and offer my support throughout the year.

Every August/September the new school year begins flooded with back-to-school nights, forms to be filled out and a hundred new things to learn and navigate. One of the most important things that parents can learn this year is how to communicate well with your child’s teacher(s) – what their style is – and how to discuss what accommodations may be needed as a Muslim student in public school.

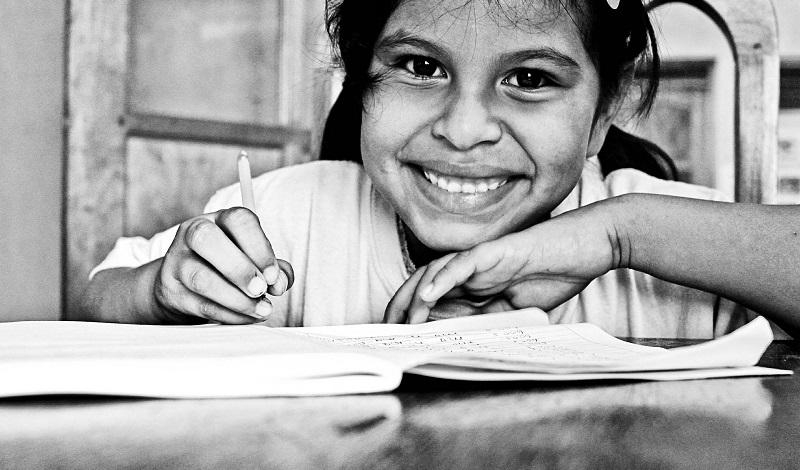

Image source: Sahar from the CBC documentary, "14 & Muslim"

Each year during the meet-the-teachers night, I discuss food restrictions my kids will have during the school year followed by a printed note or email of what they cannot eat, such as meats and gelatin. Although my kids take their own lunch, this comes up during holiday seasons and class parties, where food and treats are the norm. Overall we have not had problems, and teachers have been accommodating toward my children’s needs just the way they handle other food-related concerns for children with allergies.

I try to make it easier for everyone as well, offering to send in halal marshmallows and halal hot dogs for school activities or parties rather than expecting my kids to just miss out.

During the school year, I also explain to the teachers what activities my children cannot participate in, such as Halloween, Christmas and Easter-related activities. I make a point to educate and ask teachers to find inclusive activities without centering the activities around any particular holiday.

Not My Parents' Version of Communication

Communicating effectively with teachers depends on your intention, approach and making sure both parents and teachers are on the same page without being overbearing as a parent. Each situation will be dependent on both parties’ personalities, and the teacher’s understanding of Islam in some cases. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to communication, but rather the idea that you learn your teacher’s style for preferred communication and relay the information you need them to know.

When I was a child growing up in the 1990s, I remember my parents simply telling us not to eat pork and then not interfering in activities. They expected us to figure it out. They weren’t used to challenging the system and did not understand the public school system set-up. They were also more open to assimilation without knowing when and how to question American norms.

For example, when teachers sent letters home to bring candy for Valentine’s Day or Halloween, my immigrant parents sometimes bought candy and sent it in as instructed. No costume? They let us wear a pretty dress or salwar kameez (tunic and pants) to still participate in the class party. My parents would also never question motives behind teaching students Christmas songs in music class or celebrating Easter egg hunts in spring. They didn’t think about the underlying meaning of holidays they never celebrated or heard of or if their children were becoming confused in their identities.

This wasn’t the experiences of all Muslim communities, but it is one many immigrant and first-generation American Muslim families share.

What Makes for Effective (but Not Overbearing) Communication?

These days I find that my friends and I question these holidays more and teachers also take proactive steps to not overstep cultural or religious lines. Muslim parents are choosing to speak up, suggest alternatives and reflect more on how their children’s experiences in schools ought to be.

One of my children’s teachers a few years ago sent home a form to “get to know your child” where I wrote down suggestions for inclusive “holiday” activities, such as doing winter-themed classroom projects around Christmas time rather than all-out holiday activities or doing fall-themed activities instead of Halloween. I also wrote that since it was my child’s first year in school, she may come to school some days wearing cultural clothes and other days wearing a hijab, if she so wished.

The teacher was receptive to my feedback and asked follow-up questions to make sure we were both on the same page.

Another teacher would contact me before the holiday parties, as I suggested, and inquire whether my son could eat certain foods. I would also offer to supply a classroom’s worth of halal alternatives if needed. When my oldest was in second grade they had a hot dog party and we sent in two packets. The teacher called to ask if it was okay to share with other second graders, and they were all used. It was a win-win situation!

A lot of this begins with open and honest communication with your child’s teacher at the start of the school year, respecting their knowledge of how to teach and run a classroom and trying to be a friendly face throughout the school year (maybe by volunteering, attending school functions or just checking in occasionally) as time and energy permits.

These tactics also evolve as your child moves from elementary/primary school into middle school and on into high school. For example, with elementary school-age children you may need to speak to the teacher more directly, and have greater opportunities for in-classroom volunteer experiences; whereas for middle school and high school-aged kids, you can speak to your children about what you expect from them in school and how they can share this information with their teacher such as when they are fasting during Ramadan or need to be excused for a test day if it falls on Eid.

Sometimes, if the need arises, you can loop in their guidance counselor to help communicate these things.

Different methods of communication work with different educators. It’s important to note what doesn’t work as well as what does. Here are some of my tried methods of parent-teacher communication (and failures) over the years focusing on elementary school. Hopefully you can avoid what didn’t work and apply my more successful approaches to your own child’s school year.

Also, please note that it isn't just about conveying things about what we can and cannot do as Muslims, which is the focus of this article. These tips can be applied to how we can effectively communicate with teachers and advocate for our children in a variety of areas.

Tips for Effective Parent-Teacher Communication

1. Always establish contact early on. Attend the “meet-the-teacher” or “back-to-school” night and put a concerned face forward. (Do this in middle and high school as well, as it’s one of the only opportunities you have to make face-to-face contact with all of your child’s teachers.) Show that you care about your child’s education and that you trust the teacher to do their job to provide that. Join parent meetings and groups.

The more informed you are about how things work in that school, the more you can communicate. If you can’t attend parent-teacher association meetings, you can join a Facebook group or classroom “remind” groups to stay on top of school happenings – whatever it is that your child’s teacher uses for communication.

2. Send handwritten letters. I found that it’s best to send in a note that the teacher can see and write down a quick comment back rather than check an email. You can move to emails once you’ve established a connection.

3. Give teachers the benefit of the doubt. They may not always know or may not consider certain things when planning different activities and lessons. Don’t be afraid to educate. Your Muslim kids shouldn’t have to be left out of the consideration when class parties are planned and activities are scheduled.

For example, I tell my teachers that my kids will be fasting and to be mindful of their limitations. You may want to ask for alternatives during Ramadan (if your children are fasting) for physical education class (in middle or high school). Don’t expect that gym teachers will opt your child out. Consider asking for make-up work. We want to be fair in asking for accommodations. For my younger kids, I advise teachers on when and how to tell my kids to break their fast if they are struggling.

I’ve had some teachers who expressed understanding our family’s needs due to having Jewish family or friends who also practiced similar beliefs. Others said they have Muslim friends and are familiar with the cultures and norms. Some of my children’s teachers over the years did not know the difference between religious or cultural norms for our family due to how Muslim communities practice beliefs differently. This is all to say – let them know what is important particularly to your family, but try not to overburden them.

3. Exercise kindness. More than anything, whatever you say nicely is always received better.

4. Offer alternative options. If the class is having a party, rather than saying, my kid can’t have this or that, send in something they can all share together. Talk to your kids. Let them know they can be proud of who they are the way they are. They may feel bad and left out sometimes, but the overall reward is bigger. Even if they can’t partake with, say, the Halloween festival, if you have a good relationship with the teacher, sometimes they save candy for your kids. :)

Ask teachers to contact you if they have questions. Provide your phone number and/or email. Teachers will take you up on it! Be patient. Wait for your teacher to get back to you. Don’t pester them.

5. Be mindful of accommodations. This is super important and worth repeating. Is it reasonable? Is there a way to scale down or scale up the request to benefit more students? For example, can your school provide all Muslim students a space to sit while they are fasting rather than make a small accommodation for only your child(ren)?

Or, is the ask “too big”? My children do not partake in Halloween-based activities in school. I attended a PTO (parent-teacher organization) meeting to express that I’d be happy to volunteer and facilitate an alternative to the all-out school costume parade for families like mine. This led to confusion, and ultimately the principal (at the time) calling me and telling me that the accommodation wasn’t possible on the scale that I was asking.

I also realized that I would need a lot more concerned voices to bring to the table for any action to take place, but it would have to be at a superintendent level – a stretch to say the least. The lesson I learned? I was expecting too much or trying to ask for too much accomodation. I stepped back and asked the principal to provide an alternative for my child. He let him stay in his office and put together a puzzle during the parade.

Some years when I had a flexible schedule or worked from home, my kids simply stayed home. Other years, they stayed in school and just didn’t dress up. As long as you explain the changes to your kids, it’s okay if your family’s choices evolve over the years due to your family’s needs and capabilities. Also, many schools across the country have already become more cognizant of the diversity of students and beliefs and organize more non-religious themed events, such as fall festivals, winter parties and spring flings.

6. Send in a gift at the end of the year. Show your teachers you appreciate them with a parting gift. They work super hard throughout the year.

Photo by Zach Vessels on Unsplash.

Teachers can be great advocates for your children’s well-being and self esteem. I’ve seen teachers stand side-by-side with my children when their beliefs are questioned or ridiculed by others. Teachers over the years have been supportive and receptive to feedback, and willing to ask questions when they were unsure.

When you’re trying to best serve your children, there will always be a way to work around what you need. Don’t forget to be patient and work with the teachers rather than against them. Ask other parents for suggestions, especially if they have similar-aged kids or have gone through similar situations in the past. Offer to volunteer and show up whenever you can.

A lot of schools are open to diverse experiences and may encourage a parent reader or someone to share experiences for Ramadan, Eid and other holidays during educational or “cultural day” sessions. Other schools may take on a toned-down approach, such as providing literature in the school library for kids to read on their own about different cultures, religions and traditions (donate books!) in addition to social studies courses in school.

Whether your family wishes to take a strong stance on American Muslim identity in school or simply make sure your kids don’t eat pork in school, your role as parents helps children ease into practicing their faith in schools according to what your family is comfortable with. This also doesn’t mean that your faith is being shoved down people’s throats. Rather, it can sometimes lead to an opportunity to educate people about Islam. At the very least, simple accommodations can be made for American Muslim students just as they are made for other faiths.

Whereas many of our parents perhaps took a quieter stance on identity politics in previous decades, more Muslim parents today are more comfortable with encouraging their kids to be proud of their faith in and out of school, due to larger numbers of Muslims in some schools and/or the need for exposure to our faith to change negative dialogues about it. Ultimately though, you choose what works best for you, your family, your children and their teachers.

Let us know what are some tried and failed attempts you’ve had in communicating effectively with your children’s teachers in the comments below!

Subscribe to be the first to know about new product releases, styling ideas and more.

What products are you interested in?