How Dr. Ingrid Mattson is Confronting Spiritual Abuse through Leadership Education

Faith

|

Feb 18, 2020

|

7 MIN READ

Editorial note: This post is part of a site-wide discussion and campaign about "This is what America looks like," in which we are exploring the lives of powerful Muslim women, our activism and work and how we are standing up and showing up.

By Layla Abdullah-Poulos

Despite the beauty of Islam as a faith and way of life, there are harsh realities that come from interacting with one’s fallible co-religionists. Muslims are human and prone to gracing each other with love and compassion as well as inflicting one another with pain and subjugation. No one is immune. Adherents, leaders and scholars can all be sources of abuse, creating emotional pain and potential crises of faith.

Issues of abuse continue to plague American Muslim communities making it necessary for organizations to raise awareness through education and provide services to those impacted. The Peaceful Families Project focuses on domestic violence prevention. HEART Women and Girls raises awareness about sexual abuse and supports survivors, FACE (Facing Abuse in Community Environments) promotes safer Muslim communities by holding religious and community leaders accountable for abuse, and the Muslim Anti-Racism Collaborative provides layers of education about racism and anti-Blackness.

Dr. Ingrid Mattson; image source: Flickr

Professor of Islamic Studies, interfaith activist and Muslim leader Dr. Ingrid Mattson founded the Hurma Project to increase awareness about Muslims subject to spiritual abuse by religious leaders and scholars as well as the need for prevention, accountability and a revival of ethics among those providing pastoral care and claiming the intellectual authority to convey devotional knowledge. The Hurma Project, which recently convened its first research conference in Chicago, encourages an appreciation for humanity and agency and to uphold individual rights to dignity and honor as sacrosanct.

I spoke with Dr. Mattson recently about why she is focusing on the issue of Muslim leadership and spiritual abuse.

What motivated you to launch The Humra Project?

There are a few things. I have had to deal with a number of different situations on a case-by-case basis and tried to inform board members and get some accountability when things were disclosed. It was always on an individual basis and required a massive education campaign about the fiduciary responsibility of each organization and moral responsibility to deal with these situations.”

There is often so little accountability and supervision. We put people in positions of power and influence. We want them to have a lot of knowledge, charisma and be a spiritual force to shape people. It can be used for good or for bad, and we are so hands-off.

Two episodes drove me to take responsibility at a higher level: Seeing many of my younger friends, students and colleagues, like Nadiah Mohajir [ of Heart Women and Girls], who were responding to disclosures of abuse in a professional and compassionate manner and being ignored, shunned and attacked, was very painful.

They were taking on the responsibility of the community to do the really important work of supporting survivors and were completely demonized and subject to ad hominem attacks, denial and minimizing. It became clear to me that they needed more support, especially from Muslim scholars and those teaching about religious ethics, norms and philosophies.

So often, our religious discourse – our principles and values – were being used to demean, diminish and deny what was happening, especially in terms of sexual assault.

In 2008, a group of us was approached to support a number of well-known, competent and knowledgeable imams who were trying to deal with a major violator in their midst, and they were unable to really deal with the situation. We realized that there was very little we could do. It felt very frustrating and like our hands were tied [when] they shouldn’t be.

I realized we needed something broad and interdisciplinary to examine the scope of the problem, have a good understanding of all of the dynamics and develop educational materials and processes that we can bring to the community.

Hurma is the sacred inviolability of the person – the body, dignity, property and livelihood. I was guided to this concept [by listening] to people rationalizing demeaning women, abuse and the instrumentalization of others. It was clear to me that they had missed the whole point of the revelation when it comes to our relationships with each other. On the one hand, there is our relationship with God. Everything that happens under the umbrella of that relationship. But when it comes to all of the teachings about our communities and families, it is about upholding the individual.

Allah (S) intervenes and sent revelation so many times in response to situations when women were complaining about their marginalization and dehumanization. Anywhere someone had power over someone else, you see the Prophet Muhammad (saw) intervening and elevating that person – the blind man, the child, the person with mental disability. When we look at the Quran and interventions of the Prophet [Muhammad] (saw), we see in each case, there is an intervention to say this person matters. Their body matters. Their life matters.

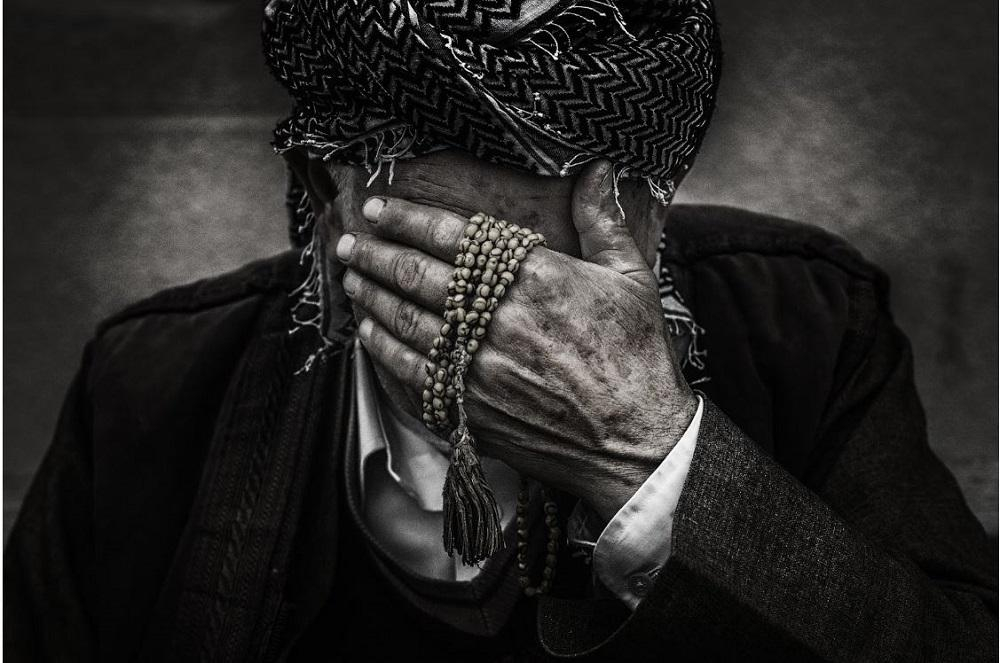

Image source: Pixabay

Islam is not a religion to elevate and put able-bodied, adult men on a higher pedestal. The patriarch is not just the male, he’s the male elder, which is why prepubescent or young boys are sexually assaulted and molested by older men.

The Prophet (saw) taught his companions that the hurma of a person is equal to the hurma of the sacred months and places. Even a dead person has hurma. That’s why we treat the bodies of our dead brothers and sisters with respect and care. The person [keeps] that sacred inviolability in death. So, how could we possibly be a community that thinks sexual assault and violence are not a priority?

What are some of the ways Muslim communities can make inroads in raising awareness about all forms of spiritual abuse?

Our first step is general education on a number of levels. What are the dynamics of power and vulnerability? It is not only in secular society. A religious leader is a professional as well.

We [also] need to bring in our history. In Islamic history, every single person had a supervisor. If they were an imam, judge or governor, they had a supervisor. There are examples, from the very beginning of Islam to the later periods, that if [someone] misused or were accused of a violation of trust, the supervisor removed them from that position and investigated. If it was found they were abusive, they were punished, if not, they were exonerated in public. Umar bin Khattab (ra) did it with Khalid bin Walid (ra).

We have to all become better educated about the social and psychological dynamics of trauma, the kinds of things that those who are experts in sexual assault or trauma and mental health experts understand.

We need to make sure there is executive authority supervising and holding people accountable and grievance processes. In some cases, it is our obligation to conceal. In other cases, it is our obligation to report. Violating someone else’s rights is subject to disclosure.

Allah (S) says in the Suratul Nisa, verse 148, "Allah does not like the public mention of evil except by one who has been oppressed." In Riyadh-us-Saliheen, Imam An-Nawawi gives five examples of when someone can disclose derogatory information – speaking to a judge, an advocate helping someone disclose a violation of their right, etc.

[One] gap is who are you going to report [the incident] to? There is an obligation in Islamic law, and there is an obligation in American law for [organization boards] to deal with those situations. So, for them to cover [it] up, they are violating a legal fiduciary responsibility.

A big part of the problem is that our communities are very small. We are very close, and board members don’t understand that they have to keep a certain amount of space between them and the religious leader. They’re too close. The head of the board may even be a student of the shaykh or shaykha. In that case, how can we expect that person to hold the shaykh/shaykha accountable if they do something wrong?

When we agree to take certain roles in society, we have to put limitations on our actions. There should be healthy boundaries.

Dr. Mattson; image source: Flickr

How important is it for Muslim scholars to educate themselves about abuse and commit to supporting survivors?

Survivors of abuse have to be included in all of our consultations. It is very traumatic for victims. They always get blamed. I feel that I have a responsibility to say to those who have gone through this, "You’re right. We haven’t done enough," [and ask] ‘What do you need from us? What are the best ways for you to deal with this?"

No one has a right to silence them. No one can blame someone who has been abused and tried to get people to take some responsibility and no one does that, so they [resort to the media] to protect themselves and others. It’s the worst option, but it is their only option. If people don’t like it, then put better mechanisms in place.

Publicize information about the availability of support. Help friends and family members understand some of the after-effects of trauma. In this area, HEART is the most amazing organization. I’ve learned so much from and consult them on the best way to do these kinds of things.

I’m still learning. Religious scholars have to acknowledge the limitations of their own knowledge and expertise. We are all receiving disclosures. I see among female scholars an awareness that we need to learn more about these dynamics. The men who get it are [those] who have pastoral care roles. Many of the men working with us are imams or chaplains. The ones who seem distant from it are the tech scholars. They are not hearing [or seeing] it in ways imams and chaplains do.

We all need to be humble. Put yourself in the seat of a student and learn from someone who knows. Scholars need to be trained and listen to experts.

Are you optimistic that things will get better?

I feel optimistic. We have mental health and increasing numbers of pastoral care professionals who can help us understand these things on social and psychological levels. We can draw from our Islamic values, the sunnah of the Messenger (saw) and what Allah (S) to find resources to help us – not just to reproduce them but to adapt them for our current environment.

Subscribe to be the first to know about new product releases, styling ideas and more.

What products are you interested in?