Diary of a Teenager – Reflections on Rohingya & Genocide in a Modern World

Current Events

|

Jan 31, 2020

|

9 MIN READ

Editor's Note: At the beginning of the month in my editor's column, I wrote about my 16-year-old daughter Amal returning from a trip to the Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh, where she accompanied her father and others on a medical mission. She shares stories from her trip here to spread awareness of the genocide Rohingyas are still enduring.

By Amal Ali

In the music world, most remember August of 2017 to be the month that Havana (by Camila Cabello featuring Young Thug) was released. If you’re like me, you remember it as the month where Taylor Swift erased everything from her social media accounts mysteriously before announcing the release date of her highly anticipated sixth studio album, reputation.

Many of us in the U.S. remember what happened in Charlottesville, VA, where violence erupted at a "Unite the Right" rally during the hot summer days of August 11th and 12th, eliciting a highly criticized response from President Donald Trump. Also that month, North America experienced a total solar eclipse, receiving widespread media coverage; and Hurricane Harvey hit Texas causing considerable destruction.

But far away from the world of pop music sensations, turmoil in American politics and natural phenomenons, one of the world’s worst cases of ethnic cleansing was happening in the little state of Rakhine in Myanmar to the Rohingya Muslims.

This past December I had the privilege of traveling to and volunteering at the refugee camps with the Deccan Alumni Association of North America (DAANA), my father’s medical college alumni group. It was his second time lending his skills as a pulmonologist in the refugee camps and local hospital and my first time going with him.

The author with her father, Dr. M. Taruj Ali and behind them Dr. Yasmin Ansari and her son Yusuf alongside refugees at a Rohingya camp in Bangladesh. Image source: Amal Ali

Throughout our time in the camps and at the clinic, we heard several heartbreaking stories about the lives the Rohingyas lived before the massacre and how quickly and brutally everything was taken away. As many of us have been reflecting on the 75th remembrance of the Holocaust, I can't get the stories told to me and what I witnessed in the Rohingya refugee camps of Bangladesh out of my head.

One such story was Hasina's, a refugee I had the honor of interviewing; she had lived in a relatively comfortable family on a farm before the genocide took her everything away from her. “My house was burned down by the military,” Hasina said.* “We had to flee overnight through forests and hills and then cross the river to Bangladesh on a boat.” Several atrocities were committed by Myanmar’s army during her flight, but the details of these occurrences are much too painful for Hasina, and many refugees like her, to revisit.

“I miss my home,” Hasina told me when I asked what she missed the most about her life before. I asked what she wished would change in the camps. She said, “The military is very oppressive to women. I am happy here with what I have, but I am vulnerable.”

Why Are Rohingya Muslims Targets?

The displacement and genocide of Rohingya Muslims represent the culmination of a long history of racial discrimination and persecution based on culture and religion in Myanmar; a timeline that started in the 1940's when Myanmar (known as Burma at the time) gained its independence and denied citizenship and legal status to the Rohingyas.

Myanmar has always had a dominant Buddhist population, making the Rohingyas an ethnic, religious and linguistic minority group in the country, as they are Sunni Muslims. However, the minority group traces back its origins in the country all the way to settlement in the Arakan kingdom in the 15th century, making them a thoroughly well-established population in Myanmar.

In the late 1980's when Burma was officially renamed Myanmar, Rohingyas were again denied their citizenship and were not recognized as an ethnic minority. In 2014 they were completely excluded from Myanmar’s national census, signifying the increasing efforts of the country’s government to “erase” the population.

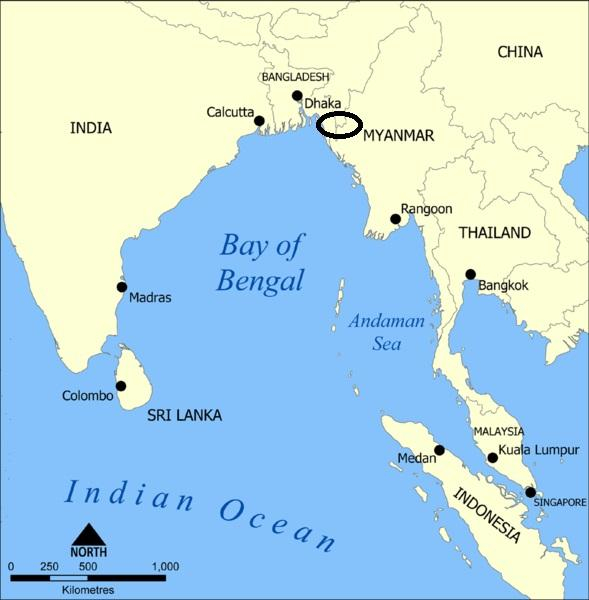

In August of 2017, a militant wing named the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) attacked some military and police outposts, resulting in the death of 70 people. This began a brutal crackdown on the Rohingyas by the Myanmar army; 7,000 were massacred in that month alone, after which 700,000 Rohingyas fled to Bangladesh. Thousands more escaped to Indonesia, India and Malaysia.

Since then the population of the Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh has increased to more than a million people. The United Nations and several charities, including DAANA, have devoted lots of time and money to the well being of these refugees.

Those Who Suffer the Most

Immediately after and during the massacre, Myanmar’s army committed crimes too horrifying to describe against Rohingya women. Such crimes are incredibly sensitive subjects for many refugees, but some yearn for their stories to be heard. On our last day in Bangladesh, my father and I spoke to Ayaz Mahamud, who is a social worker with Terre Des Hommes and is dedicated to assisting rape and sexual assault victims in the camps. He told us the stories of two women in the camps, whose stories represented the thousands of women assaulted by the military.

“A lot of these women suffer from mental illnesses because of what they’ve been through, like post traumatic stress disorder and eating disorders,” Ayaz said. “Many of them cannot sleep at night either because they hear the sounds of bullets whenever they close their eyes.”

After the massacre, many children had been so traumatized that they seemed to develop undiagnosed mental disabilities very similar to autism. Ayaz told us that when he went to the schools and asked some of the Rohingya children to draw for them, they would draw horrifying scenes from the massacre depicting weapons, death and destruction. It was the only world that they knew.

A Rohingya refugee child's drawing of the genocide. Image source: Amal Ali

Many children also drew their family relatives, who passed away in the genocide.

Earlier before we met Ayaz, we had traveled into the camps, which was where we met Hasina. While in her home, I tried to speak with the large group of children who had huddled behind the window to listen. Through their broken English, there was one phrase in particular that we could decipher, and it was thoroughly chilling to hear, “I will kill you.” Many children said it with a laugh.

I realized that perhaps this was a phrase they heard from the military when they were fleeing, and it was some of the only English they could remember. It was obvious that the children did not know the meaning of what they were saying, and it truly broke my heart once I connected it to what they had been through.

Ayaz told us about another incredible woman, Mumtaz, whose story of her flight from Myanmar reveals the true nature of the massacre. “She heard gunshots in the night and immediately started to run with her children and husband,” Ayaz recalls. “She tried to cross the river, but it was too difficult to do with four children. Where she was stopped is now the site of a mass grave that the military started digging that night.”

We even went to a section of this river one day during our time in the refugee camps and tried to imagine what had happened on this body of water three years ago. It was simply chilling.

The more I hear the stories, the more livid I become that Myanmar’s State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi still continues to deny that a genocide even occurred in the first place at the International Court of Justice. Her Nobel Peace Prize, awarded to her in 1991, needs to be revoked.

The details Ayaz shared with us about what happened afterwards are nearly too horrendous to share. Babies snatched from mothers and thrown into rivers, one of them being Mumtaz’s son. Homes being set on fire and military officials throwing people into the fires. Men being lined up on their knees and shot dead, one by one. And, women stripped of their valuables and then assaulted and raped while their family members were forced to watch.

When we visited a hospital established by the HOPE Foundation in Cox Bazar, we met Syed Fakhrul Huda (Fakhar), who told us about the awful things refugees experienced after those who survived crossing the river first arrived in Bangladesh. “Since they were technically encroaching on the natural habitat of the elephants, several were trampled and died,” Fakhar said. Imagine surviving a massacre only to be killed by the elephants when you finally found somewhere you thought you could be safe.

Rohingyas crossing the Naf river between Myanmar and Bangladesh. Image source: Twitter

“It was a very, very long time before the camps reached a point where they are today. Initially people were just sleeping on the ground, and several got sick and died very quickly,” Fakhar added. “The camps you see today, with field hospitals and food distribution and wells, looked nothing like this even a few months ago.”

Even though the camps I visited were much more organized with huts and even a small shopping market, our homes in America are complete palaces compared to the living quarters in the camps. The huts barely cover half the space of the smallest New York City apartments, and they have no semblance of kitchens, bathrooms or bedrooms. There is no sense of sanitation or hygiene requirements. There is no heating or air conditioning. We live like kings and queens compared to the families we met.

It is something we must remember when we ponder when we will get the next iPhone or what outfit we want to buy next.

A Dire Need to Spread More Awareness

There is one thing in common with all of the interviews we conducted in Bangladesh – every single person said they wanted more awareness spread throughout the world about what was happening to Rohingyas. “We simply want more people to at least acknowledge the horrors that have occurred here,” Ayaz said. “There was news coverage in 2017 when the genocide first occurred, but barely anyone knows the magnitude of the camps here and just how much poverty there is. We need more awareness.”

Another detail I noticed in relistening to the interviews we conducted was the haunting similarities between the events of the Rohingya massacre and the events of the Holocaust, or even what slaves had to endure on their the long passage to America in the late 1500's and early 1600's. We spend a lot of time asserting that we can never let history repeat itself. We say #NeverForget all over social media, and yet here we are.

If religious discrimination was no longer a threat in this world, then there would not be more than a million refugees in this camps, and there would not be concentration camps in China, and the Indian government would not be able to selectively deny citizenship to Muslim refugees.

Yet, here we are.

I write about Rohingya refugees with a deep, deep hope that Insha’Allah I can do just what they yearn for – spread as much awareness as possible. I also hope that raising awareness about the issue can show the world just how much work we have ahead of us in this new decade. For in the stories of those in the Kutupalong camps, there is a somber reflection on what awful problems our planet still struggles with.

Let me say it again: We have a lot of work ahead of us in this new decade.

Let us begin by laying in bed tonight and thinking about all our blessings – our warm beds, closets full of clothes, dinner on the table, financial security, clean water – all of it. Let us wake up tomorrow morning with the resolve to treat those who are deemed “the undesirables” of our world with a little more love. For at the core of every soul is a yearning to be loved.

*Quotes were translated as they were originally spoken in a Rohingyan dialect, so they are as accurate of an approximation we could get.

Amal Ali is in 11th grade at a high school in Virginia.

Subscribe to be the first to know about new product releases, styling ideas and more.

What products are you interested in?